Scott Graham - Your First Pair of Overalls

Edition 3: Preamble 1

Welcome back to Behind the Throttle! Our third edition will formally begin in January 2026 – but before then, we have a few mini-stories to set the scene. Railroading is an industry like no other, with an intimate and honest culture that turns the craft into a lifestyle. Our story today takes a look at someone’s introduction to the world of railroading, and what they learned about being a railroader in their short stint working for the Denver and Rio Grande Western. Today on Behind the Throttle, let’s meet Scott Graham and his first pair of overalls.

“I was welcomed into this well-oiled machine that was the Denver and Rio Grande Western…and what an honor!”

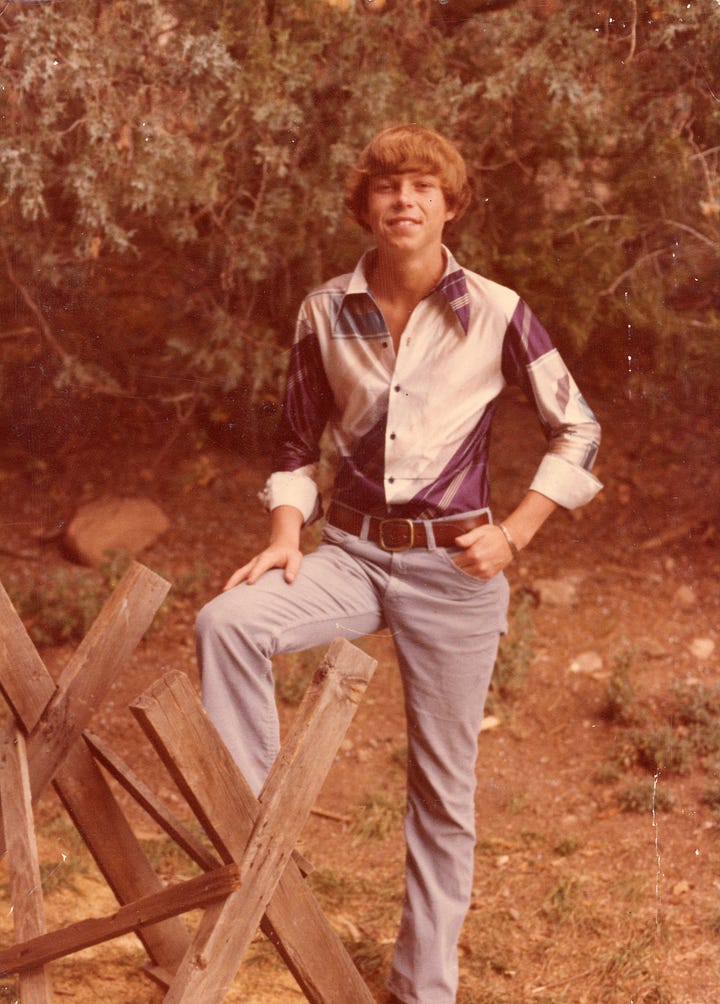

It’s June 1979 in Durango Colorado. The air is warm, the town is teeming with tourists, and blue smoke is belching from the tailpipe of Scott Graham’s International Travelall as he trots home from a day’s work. His overalls are heavy with coal soot and grease, and his hard hat has deteriorated from its bright blue color to a dark shade, withered from months of tending to three locomotives that became his livelihood. Totally green to the world of trains and railroading, Scott found himself with the opportunity of a lifetime in between semesters, working on one of the most storied railroad branch lines in the American Southwest – an opportunity that he took, loved, and then left behind.

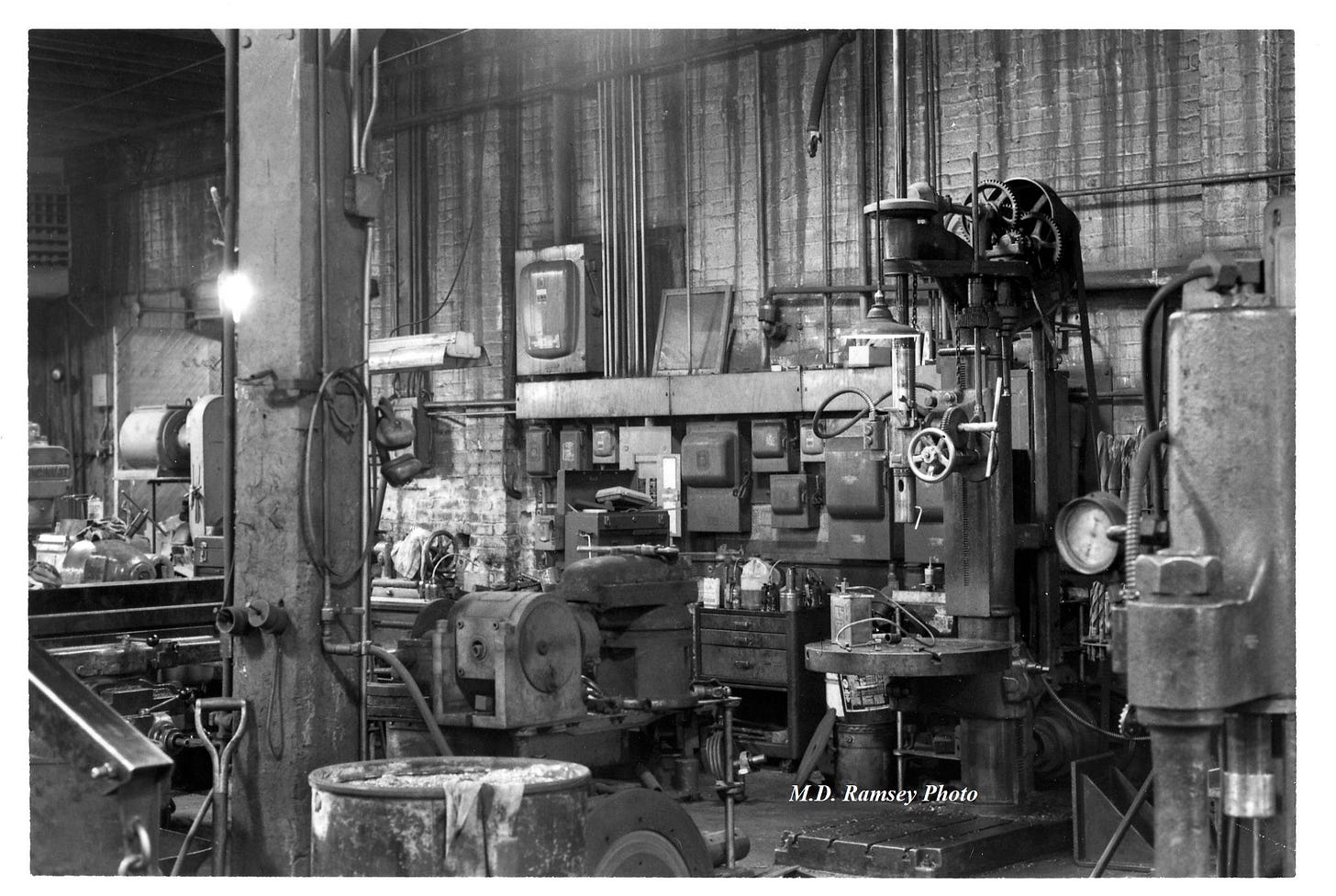

Growing up in Durango, a locomotive’s whistle was never far off. The Silverton branch of the Denver and Rio Grande Western has been running continuously since 1881, hauling freight and mining ore between the two towns on a narrow gauge line through some of the most beautiful – yet treacherous – terrain viewable by rail. The scenery would lead to the eventual tourist-ification on the rail line and surrounding town, keeping the railroad running far past the freight and mining downturn. Scott spent his summers in high school around the train, working in what was called the “Coke Car” – the name for the train car that would sell snacks and Coke products to passengers onboard. Scott considered his role in the Coke Car a thrill, but he had no idea what would come next: The illustrious opportunity to sweep the shop floor of the Durango roundhouse! It may not sound appealing to most – but to Scott, this was his foot-in-the-door to a grand operation. A curtain had been lifted from him as he entered the roundhouse for the first time in 1979 as an employee, proudly wearing the boots, bib overalls, half-sleeves, and gloves that he bought with money borrowed from his parents.

The Memorial-Day-to-Labor-Day schedule of trains meant that many tenured (or senior) employees of the D&RGW would bid to work in Durango for their summers, mostly coming from the shops in Alamosa, Colorado. The guys that would bid out would spend the first few weeks of their time in Durango performing maintenance and tests on the three class K-28 class steam locomotives that were the entire operating fleet of the railroad. The rest of summer would be spent catching up to the engines with the never-ending battle of maintaining a steam locomotive. The shop team also shared in the responsibility of operating the engines on the railroad, with many of the employees being both engineers and firemen, trained in the art of steam railroading from the country’s last holdover of the craft.

Scott’s low position on the totem pole had him working as a general laborer, but his curious mind helped him gain a keen understanding of the shop and the operation. He worked as a machinist’s helper, and saw how bits of metal could be crafted into a crucial part for the analog locomotives. He cleaned the engines and studied the machinery up close. He talked with men and women that were his coworkers, and listened as they told stories from lifetimes ago. His coworkers – mostly Hispanic folks with railroad careers longer than Scott had been alive – loved to pick on “the classic college kid”, as Scott identified himself. He remembers that they would all bring in elaborate lunches and eat family style, and that he one day was fed a radish that – unknown to Scott – was hot enough to melt steel (to him at least). Red-in-the-face and eyes watering, Scott ran around the roundhouse in a desperate search for water as his coworkers all cracked up together, saying something along the lines of “College boy can’t eat a radish!” Scott laughed as he recounted this memory, and was just glad to be at the same lunch table as these accomplished people that spent their lives railroading. Their reality was intoxicating to Scott: The locomotives, the storytelling, and especially the culture.

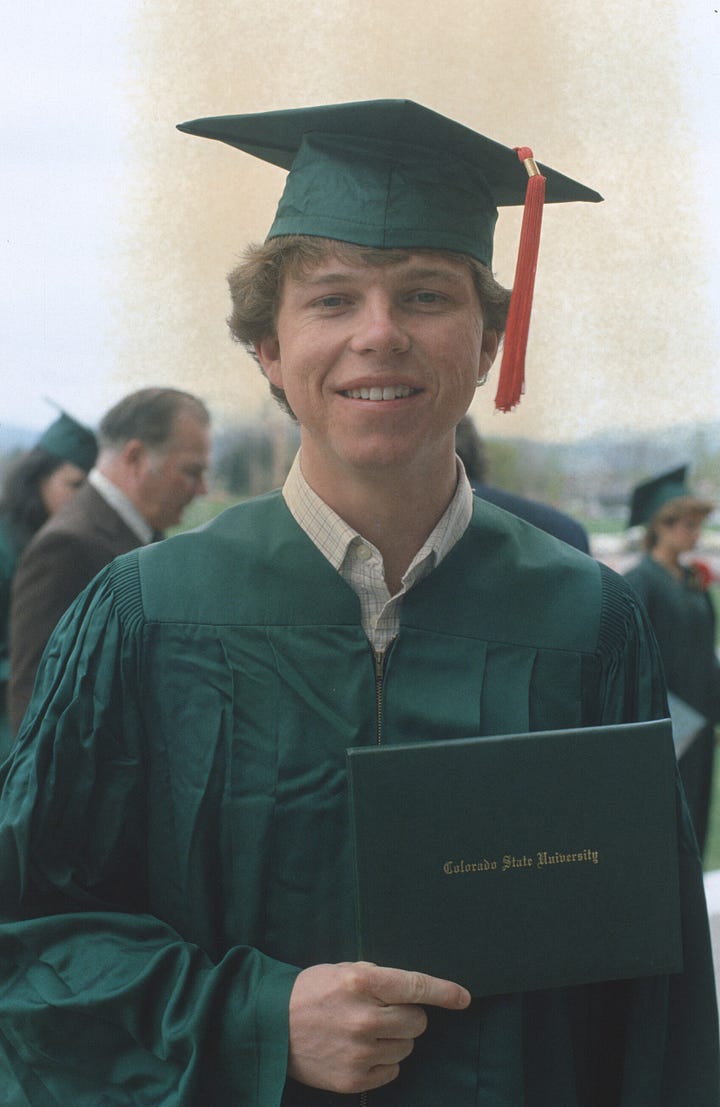

Summer of 1980 brought Scott back home to Durango after his sophomore year of his journalism degree, and he once again donned the overalls and hardhat. Making somewhere around $9.00 an hour, Scott was doing well for himself, but always opted to pick up extra hours with the hope that the railroad job would help settle his student loans shortly after graduation (a goal he was able to accomplish). His hunt for extra hours landed him the role of nightwatchman a handful of times where he would work overnight in the roundhouse and tend the fire in locomotives before their next day of operating. With only three locomotives and two trains leaving Durango daily, the locomotives stayed under steam for almost the entire Summer season. Working this shift taught Scott that firing a locomotive is much more than blindly throwing coal into the firebox, and to move a steam locomotive takes a lot more finesse than just stepping on a gas pedal. Scott described working these nights as “magical”, where he was surrounded by the silence of the locomotives simmering under the abundant stars that peered down on the little mountain town. He also recalled one night where that aforementioned silence was turbulently interrupted by the shriek of the whistle from one of the engines. Running to investigate, he discovered that someone had climbed into the cab of the locomotive and tied the rope for the whistle down, sending 190 pounds of steam through the brass chambers of the noise-making device. The longest 30 seconds of Scott’s life were spent untying this simple – yet effective – prank; To this day he still has no idea who pulled off such a devious scheme!

Some of the D&RGW employees that bid to come to Durango were enginemen from around the railroad’s system that came to briefly experience the operation. Many of them – upon realizing that fireman would need to shovel about five tons of coal every day – would pack their bags after a week and return to the mainlines where diesel locomotives were the status quo. One of these situations created a vacancy later in the Summer of 1980, and Scott was elected as the best available candidate to man the scoop. He reported to work the next day, and ascended to the cab of a 1923-built locomotive that suddenly felt like a spaceship to him. His coworkers had given him a crash course on how to fire the road, but Scott had never taken a locomotive outside of yard limits before this day. Alone in the cab with a stoic engineer, his train left Durango and Scott shoveled for his life, remembering the patterns he had been taught and reading the fire for holes where the fire would draft better and eat through the coal faster. Arriving at the first hill on the railroad, Scott’s pressure gauge began to read lower and lower, prompting a glance from his engineer that he knew meant “Fix it”. Using the thin coal dust from the bottom of the tender, Scott threw in scoop after scoop and ignited the fire enough to recover his steam and get the train over the hill. He didn’t get any more glances for the rest of the day, indicating he must have done an alright job. Scott took an engine over the road a handful of times later that summer and the next, which to this day are the highlights of his railroad career, and some of his most fond memories of his life.

The good union wages, home-cooked meals, and storied line of work kept Scott coming home to Durango for three summers. His time working in the roundhouse opened his eyes to a world of machinery, ingenuity, and grit that he previously had no thought of. Past his graduation though, the Silverton Branch was sold from the D&GRW and a new era of the railroad was coming in. Scott was offered a shop job in Denver on the D&RGW, and opted to try it for a few weeks before he decided he’d rather pursue an opportunity using his degree. He elected to end his railroad career and began to work as a corporate communication writer for Xcel Energy – ironically, writing about the utility company’s large boilers and generators, something he had gotten to be quite familiar with! Past his railroad career though, Scott felt tied to this industry, and the romance of railroading and trains is yet to be lost on him. He and his wife spent lots of time traveling internationally aboard trains, seeing the appeal of taking in the scenery and meeting others on a shared journey. Now retired back to his hometown, Scott still smiles whenever he hears the train go by, and makes a point to ride along with his former employer once a year. The railroad and the fraternity of railroaders that took him in will always be a cherished part of his life, and knowing that little pockets of community exist within trade keeps Scott curious about the journeys that we are all on.

Thank you to all our readers, and thank you to Scott Graham for joining us on Behind the Throttle. Next Monday another story will publish, further discussing the intoxication of railroading through a personal story – though from the other side of the world. Until then, I am Max Harris, and I’ll see you all down the line.

Absolutely wonderful to be featured in Behind the Throttle, Max. Thank you for your great telling of my story. I can smell the coal and grease scent of the old D&RGW roundhouse even now!