Mike May - Over the Road

Behind the Throttle: Edition 2, Installment 8

“Actually running (a locomotive) is 10% of the job, knowing how to get over the road is the other 90%.”

Today I’m excited to spotlight another person that I feel lucky to call a coworker and a friend. Railroaders with enough miles under their belt to circle our planet a few times often have encountered issues en route that have caused them to think both critically and quickly. The idea of not only knowing how to move a train, but also how to adapt and overcome to difficult circumstances, is what defines the job of a railroader to this spotlight. Today, we meet Mike May: Over The Road.

Interviews here at Behind the Throttle typically take place through phone and computer screens, but given that we’re practically neighbors, Mike May and I met in person at a mutual favorite spot for beer. Animas Brewing Company is ironically located in the former Maintenance of Way building for the Durango and Silverton, alongside the right-of-way that would build Mike’s foundation of knowledge and passion of railroad operations. But, more about that later.

As a child, Mike’s fascination with trains was quick to develop. The mainline of the Burlington Northern was right down the street from his childhood home near Chicago, Illinois, and the literal onslaught of trains that would race by always had Mike running trackside to watch and wave. Mike’s parents did not share in his blooming fascination, but his dad was keen on museums, which brought the May family to the Hesston Steam Museum in Hesston, Indiana. Here, Mike first saw steam power - both in a railroad sense and in industrial applications - and felt his interest grow in the direction of old things. He also remembers the eventual family trip to the Illinois Railway Museum in Union, Illinois, and was immediately drawn to the shop where the steam engines were stabled and maintained. The artful nature of the old machinery, with all of the moving parts that were openly displayed as they transformed steam into movement, captivated him and invited him to learn more from a young age. As Mike grew up, he continued to find new hobbies - mainly a passion for theatre that would guide his future studies - but his interest in trains kept growing on the side. Trains took a side-step for Mike throughout high school and his first few years of college, but as he felt more and more smothered by his schoolwork he rediscovered his passion for railroads as a means to diversify his time and escape from the ordinary.

Mike would soon drift back to the Illinois Railway Museum, now as a volunteer, and found himself soaking up information and learning whenever he could. Coming back to the IRM, Mike knew exactly where he wanted to dedicate his volunteer hours. He recounted his train of thought: “If I’m gonna do this, I have to be around steam”. His enthusiasm was greeted with opportunity, and the overwhelming amount of knowledge in front of him was “shocking”, as he said. After lending a capable hand where he could in maintaining the IRM’s 2-10-0 No. 1630, Mike found himself riding along on the engine’s excursions on the IRM track before long. Mike had been in the cab of a locomotive before, but never out on a railroad where got to see the art of operating steam close-up. He remembers watching the fireman dance around the cab, masterfully placing each scoop of coal with precision, and watching the locomotive’s pressure gauge react. He similarly watched the engineer dance between controls, using throttle and air simultaneously to give the passengers a smooth ride and keep the train on it’s schedule. Mike had found the spot where he wanted to learn, and was naturally offered the opportunity. From there, Mike began to learn the art of firing, and this introduction to railroad operations were scratching an itch that Mike never new existed. As he saw more and more systems of a railroad come together from his time volunteering, he felt strongly that it was worth immersing in. Beyond his college graduation, Mike worked briefly in the theatre world but hoped to dive more into trains; He therefore sent his resume around to several of the railroads that at the time ran steam on a near-daily basis. The Durango and Silverton was the first to respond, and invited him to a job fair to learn more about the company and talk with supervisors. He would leave Durango from his first visit with a start date on the railroad, and returned to the small mountain town to begin this new chapter.

In 2005, with his graduation from university not far in the past, Mike packed up his car and headed southwest from the Windy City. Anticipating on spending just one summer out in Durango, Mike did not have much expectation for what his job would look like, but was excited nonetheless. The premise of seeing a large-scale tourist railroad, still abiding by the railroad practices and motive power of a time a few generations before his, was an opportunity he couldn’t pass up, and being involved in any way felt like a victory. His first summer was spent mostly working as a brakeman, onboard the daily trains to Silverton and making sure the few hundred passengers transported each day had a memorable and safe trip. Within this role, Mike got familiar with a lot of old school railroad practices - hand signals, flag protection, retainer valves and more are all status quo at the D&S, and their rulebook and operation infatuated Mike. Before his first season was over, Mike was offered a chance to fire, an opportunity he jumped on quickly. His previous experience firing at the IRM provided a good foundation of knowledge as he re-entered the craft, but nothing really could have prepared him for shoveling several tons of coal up a 45-mile railroad that was practically all sitting on a 2.5% grade. After a handful of student trips, Mike was given the scoop on his own and began the time-honored tradition of carrying trains on his back from Durango to Silverton, a job he was proud to have.

Mike returned to Illinois for the winter of 2005-2006, but found his way back to Durango the next summer. This time, however, he would be staying. Having fallen in love with the romance of rocky mountain railroading, Mike decided to commit a few years to the D&S and continued to fire and work with passengers. In 2008 he began as a student engineer, and was promoted to engineer that next year. His first few experiences running were “terrifying”, as he described it, but a welcome challenge. He made his intentions of becoming an engineer aware from his first day in Durango, and the railroad was quick to help him achieve this goal. Throughout his time marking up, Mike encountered several mechanical issues that are frequent with old trains and equipment (ironically, the diesels owned by the D&S at the time were more troublesome than the steam engines). This proved as a learning opportunity though, and Mike soon found out that being an engineer means much more than just driving the train: “Actually running is 10% of the job, knowing how to get over the road is the other 90%.” Having an understanding of the machines he operated, and knowing how to troubleshoot to make sure he didn’t maroon 300 people in the Animas Canyon quickly set in as the primary responsibility of being an engineer, and he took the role seriously in that he wanted to make sure he could always deliver his passengers to where they were going, ideally with a smooth ride. In his time as an engineer on the D&S, Mike had everything but the dining car sink thrown at him as he railroaded through the Rocky Mountains. Every challenge and every breakdown was a chance to learn and experiment, and his ability to bring his trains home regardless of what happened on the road was a point of pride in his career.

Around 2010, after six summer seasons on the Silverton, Mike began to look outward for a new opportunity. Though grateful for his time in Durango, Mike was curious to find a new operating challenge and began talking with some of his railroad friends who then worked for Amtrak. They encouraged him to put his name out there, and Mike obliged after a short while. He applied to crew bases around the country, but his hometown of Chicago was the one that gave him an offer. He gave his notice in January of 2011 in Durango, and made his way east to Wilmington, Delaware, for Amtrak Engine School. His time in Amtrak’s training program was vigorous, but enjoyable. Mike grew to be quite fond of learning new rulebooks and operating guides, and learning Amtrak’s rules of the road was quite interesting to him. Mike also grew to be friends with most of his classmates, and they would often take the train to New York on their weekends and explore the city. After passing the class with flying colors, Mike went home to Chicago and began to run for America’s railroad. His time as a student was spent on the various routes that Chicago-based engineers need to run, traveling some of the busiest rail corridors in the country. After a few months, Mike marked up and had his first job running the California Zephyr on the Ottumwa Subdivision, west from Chicago. Mike remembers this job being especially unpredictable because of the railroad’s physical characteristics, but also with the frequently late Zephyr coming back east that he would take home. Regardless, Mike grew to love the route and still thinks of it as one his favorite stretches of railroad he has operated on.

As Mike gained some seniority from his position with Amtrak, he was given the option to bid for a job that would give him some consistency in his schedule. However, he opted to stay working on the extra board, where he worked on-call. This spot gave Mike the ability to run a different train every day and learn how to run more than just a single assignment. Being on the extra board also allowed Mike to work some of the random and unique trains that would come through his territory, including Amtrak’s Exhibit Train, a traveling museum that went around the Amtrak system for a handful of years. The extra board had Mike also qualify on some stretches of railroad that other Amtrak engineers couldn’t run on, and gave him a chance to work odd trains from other railroads and operators. Mike was especially grateful to be on the extra board when the Nebraska Zephyr, a vintage trainset restored by the IRM led by a vintage E5 streamlined diesel, made excursion runs from Chicago to Qunicy, Illinois, in September of 2012. Working with one of the engineers that trained him, Mike and this senior hoghead worked for a long weekend aboard the sleek trainset as it moved at the same speeds it would have back in the day, on the tracks it was built to operate on. Mike recalls some trouble with the folks in charge at Amtrak about running the trainset, given it has a unique airbrake system that was unlike what could be found on a modern locomotive. His mentor and now colleague dismissed the concerns, saying something along the lines of “It’s an airbrake!”, to which Mike added: “If I can figure out the brakes on a steam engine I’m sure I can do this”. The idea of getting trains over the road remained especially poignant with his extra board role, and Mike figured out lots of little troubleshooting tricks for locomotives and learned how to run some equipment on the fly as result. He remembers one day where he as running in a snowstorm, and his unit’s horn became inoperative as snow plugged the bells. After requesting a ladder from the dispatcher so he could thaw the horn with a fusee, he learned that a replacement locomotive would be waiting for him at the next station instead. The BNSF unit was a “SD-whatever-the-heck” with fresh paint that could still be smelled from inside the cab. After the BNSF crew handed him the locomotive that was completely alien to him, he got the signal from his conductor to depart. Mike had to take a second, saying to his conductor “Hang on, I have to figure out where the horn lever is on this thing!” He eventually figured it out, and got the train to it’s destination with minimal delays and a new locomotive in his arsenal of engines he’s operated.

After four years of running for America’s Railroad, Mike was satisfied with what he had experienced and felt ready to make a change once again. He began developing a sort of “reverse homesickness”, where he missed the Colorado lifestyle that became a haven for him. Around that time, a job had opened up at one of the sister companies to the Durango and Silverton, Rail Events Incorporated. REI is the company responsible for licensing popular themed train rides around the world, including The Polar Express. The company puts out the licenses, and then helps execute the event across the system during show season. Mike’s background in both railroading and theatre made him an obvious candidate for the job, and he remembers being courted by some of his friends and former coworkers out in Durango to take the opportunity. He gave in to their persuasions after a visit back to Durango, and put in a notice at Amtrak in Autumn of 2014. During an exit-interview with his soon-to-be former supervisor, Mike mentioned what new opportunity was taking him from a job that most people retire from. After explaining Rail Events Inc to the supervisor, the supervisor asked “How can we do something like that at Amtrak?” Before his start date, Mike had already began a new chapter for REI, but more on that later. Mike returned to Durango in November of that year, and his homecoming to his home-away-from-home was a welcome occasion. Before long, he was given the ability to mark up once again as an engineer on the Durango and Silverton, and maintains the skill of running trains at the railroad he first few in love with.

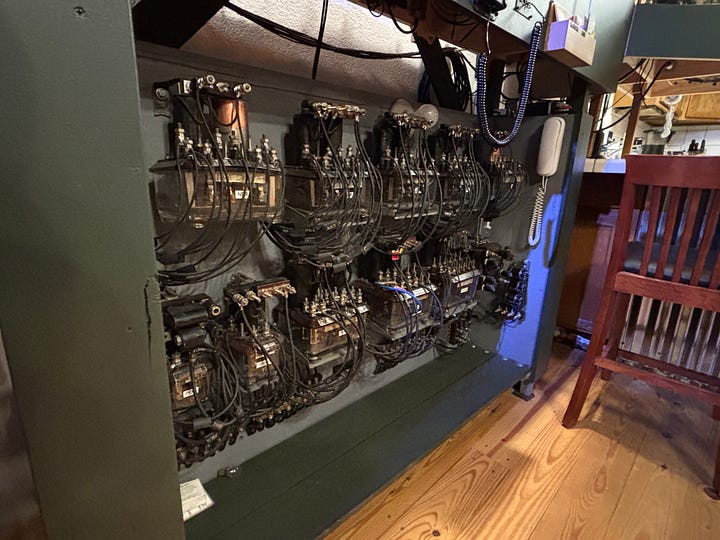

I’d be remiss to not mention the unbelievable model railway Mike constructed in his free time (when?). After learning about the infamous White Pass and Yukon Route from coworkers at the D&S, Mike made a trip out to Alaska to see what the railroad was all about. It took about 20 minutes for Mike to totally fall in love with the operation and he quickly decided that the railroad was worth fixating on. After researching the history of the line some, Mike stuck with this fascination and made the White Pass his “hobby” railroad, while other rail lines would be his offices. Always a fan of the artistic side of life, Mike had wanted to build a model railroad that was truly an homage to a certain stretch of railroad, with scenes that could be mistaken for the prototype when photographed from the right angle. Landing on a stretch of White Pass as his inspiration, Mike began building his layout in 2011 in sections and continued it’s construction all throughout his time working for Amtrak. The layout survived his move out to Durango and now resides in the main living space of his townhome. Complete with theatre-lighting to illustrate time changes and weather, circuitry from real railroad equipment, a full dispatching system with wires suspended by codeline insulators, and more gimicks that make you question if Mike is actually the railroad incarnation of Willy Wonka, the efficiently-built layout is a playground for everything Mike loves about rail operations. He even has a timetable for the layout! The layout has gone on to win several awards from model railroad organizations worldwide, and has been featured numerous times in craft magazines and journals.

Mike’s position now with Rail Events Incorporated has him travel the world to every Polar site throughout the Christmas months. He is grateful to work in his role as he feels that tons of people gain their first exposure to trains or their local railroad museum through the events, but also is grateful that Polar often times helps smaller museums and organizations fund their restorations and projects that otherwise might not be financially possible. As mentioned earlier, Mike’s Amtrak connections helped establish Rail Events Productions, a secondary company from REI that actually puts on the Polar Express event at a host site, namely within Amtrak terminals in major cities. These events draw tons of traction and similarly introduce many faces to the magic of railroads and theatre, and hopefully help develop happy memories (and maybe even lifelong passions). Mike still runs on the Durango and Silverton often, and also makes trips out to the Steam Railroading Institute to operate the 1225 (ironically, the engine that inspired the original novel “The Polar Express”) to maintain his mainline engineer card. Even further from home, Mike travels down to Australia often to operate trains on the Puffing Billy tourist railroad as a part of their international volunteer program. Every busy, but every grateful, Mike is glad to have made the railroad lifestyle his own.

As the world of trains continues to evolve and change, Mike sincerely hopes that the art of railroading is never lost. The articulate and artful nature of locomotives is what got him involved in the first place; Seeing the craft in all of its glory as engineers, firemen, conductors, brakemen, welders, machinists, roadway workers, and more find unique ways to manipulate steel, steam, and the natural forces of our universe is an idea worth protecting. Computers and technology do have a rightful place in our modern world, Mike feels, but he also believes that engineers should know how to run their trains with throttle and air alone. Mike also remarked on his hopes for preservation to keep preserving, noting that he hopes “the engines that are 100 years old now will be 200 years old and still running”. Overall, it’s the beauty, the storytelling, and the passion that inspires Mike to sit behind the throttle, and he hopes that getting trains over the road remains the artful - yet gritty - skill he learned once ago.

Thank you all for reading this edition of Behind the Throttle, and thanks to Mike for coming on with us! Tune in next edition for a look at the life of Jason Johnson, a railroad preservation heavyweight and specialist. Until then, I’m Max Harris, and I’ll see you all down the line.